Canadian scientists and researchers rejoiced last October as Justin Trudeau and the Liberal Party claimed victory in Canada’s 2015 election, signaling a potential end to a decade of fiscal austerity that has bedeviled federal researchers as well as scientists seeking federal funding. Now, a year into the Trudeau Administration, we assess whether the administration has lived up to the hype—and what the future may bring.

An Emphasis on Science

November 2015 saw a series of appointments and messages that signaled a shift away from the anti-science policies of the Stephen Harper Ministry and a prioritization of scientific research at the national level.

“The first sign that we could expect change was that the word science appeared in two different ministries,” quips Bernard Robaire, PhD, McGill University.

“The first sign that we could expect change was that the word science appeared in two different ministries,” quips Bernard Robaire, PhD, McGill University.

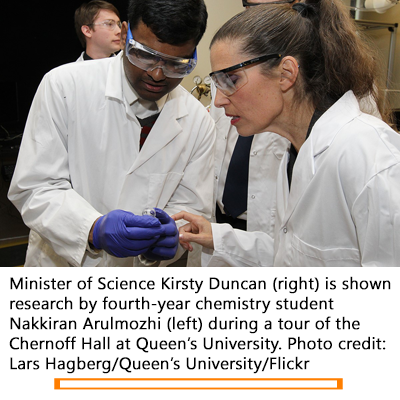

Within days of taking office, the Trudeau Ministry appointed Kirsty Duncan, PhD, to the cabinet as minister of science, a position which had been eliminated by the previous administration in 2008. Dr. Duncan was tasked with coordinating federal support of basic science research. Applied sciences also received a nod, as the minister of industry post was renamed minister of innovation, science, and economic development, which many observers felt was a move intended to acknowledge the role of research and development in industry, while the minister of environment became the minister of environment and climate change

Beyond these changes, newly appointed Minister of Innovation, Science, and Economic Development Navdeep Bains, MBA, CMA, declared in a November 2015 statement that federal scientists could speak freely to the media, in contrast to the Harper Ministry’s practice of silencing government researchers, particularly over issues of climate change. A formal communications policy was adopted by the Treasury Board in May 2016, which indicated that scientists were free to present their findings to the public and the scientific community.

Current biology PhD student Jessica Leung, MSc, University of Waterloo, says, “People at provincial and federal branches seem to be generally happy and optimistic—a feeling they haven’t felt in a long time. It looks like there are a lot of positive environmental changes happening and some restructuring.”

Current biology PhD student Jessica Leung, MSc, University of Waterloo, says, “People at provincial and federal branches seem to be generally happy and optimistic—a feeling they haven’t felt in a long time. It looks like there are a lot of positive environmental changes happening and some restructuring.”

Funding Injections

To many scientists, changes to minister titles, while encouraging, aren’t as important as budgetary support, and the Trudeau Ministry needs to make good on its campaign promises to end the decade-long draught of federal support for scientific research and education.

The 2016 Federal Budget released in March 2016 provided immediate injections of $30 million each to the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), $16 million to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), and “$19 million for the Research Support Fund to support the indirect costs borne by post-secondary institutions in undertaking federally sponsored research.” Additional multimillion-dollar infusions were provided for Genome Canada, The Stem Cell Network, The Centre for Drug Research and Development, and other federal research institutes that have languished in recent years from a lack of operating funds. “These types of projects make for great ribbon-cutting ceremonies, but haven’t been funded sustainably in the past,” explains Dr. Robaire. “There’s the appearance of a lot of opportunities, but there’s a lack of coordination behind it.”

The budget also resurrected abandoned initiatives, such as the “Post-Secondary Institutions Strategic Investment Fund.” With the new budget, Canadian universities and colleges will receive $1.53 billion over two years to upgrade and retrofit research facilities and to develop entrepreneurial incubators on college campuses. Then, in September, an additional $900 million was allocated to 13 major projects at Canadian research universities, paid out through the Canada First Research Excellence Fund established in 2014. Although this amount far exceeds the provisional $200 million yearly budget of the program, Ted Hewitt, SSHRC president and chair of the Canada First Research Excellence Fund Steering Committee, said in a press release that the investment “enables our leading postsecondary research institutions to capitalize on areas in which they excel.” Finally, in early October, it was announced that the province of Alberta will receive “$500 million from the Government of Canada, the provincial government, the institutions themselves, and private donors” for modernizing post-secondary institutions.

Jennifer Ann Love, PhD, University of British Colombia, is excited that the Trudeau Ministry seems to appreciate basic science research: “I’m encouraged about what the federal government is saying, for the most part. They seem to be acknowledging that funding levels are not at appropriate levels and that innovation (i.e., academy to industry) is not the be-all-end-all of academic research. It’s too early to know how this will translate into new money or opportunities.”

Jennifer Ann Love, PhD, University of British Colombia, is excited that the Trudeau Ministry seems to appreciate basic science research: “I’m encouraged about what the federal government is saying, for the most part. They seem to be acknowledging that funding levels are not at appropriate levels and that innovation (i.e., academy to industry) is not the be-all-end-all of academic research. It’s too early to know how this will translate into new money or opportunities.”

Patrick Pathammavong, MS, a recent graduate from University of Waterloo, shares, “Now that Prime Minister Trudeau is in power, it seems that there are more opportunities for science, but the cuts done by previous Prime Minister Harper unfortunately affected the students still working towards their degrees.”

The Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada (PIPSC, a national union of public sector scientists, technologists, and other professionals) campaigned against Prime Minister Harper during the 2015 election, citing Canada’s slumping rankings among comparable OECD countries in areas of research and development expenditure as indicators of the ministry’s failure to support Canadian science. The group’s most recent consultation report for the 2017‒2018 budget calls the 2016 budget “a promising step forward for government science,” but cautioned that “there remain many long-standing concerns to be addressed.”

The PIPSC budget consultation pointed out that while the new communication rules for federal scientists were a step in the right direction, their “implementation remains uneven across science-based departments,” and “scientists are still being prevented from participating in conferences that allow them to engage with the broader scientific community. Moreover, there has been no indication that the government intends to enshrine the principles of scientific integrity in collective agreements, meaning there are no enforceable safeguards to protect against future anti-science governments.”

Beyond their concerns about communication policies, PIPSC advocates for the hiring of at least 1,500 federal researchers “to reverse the impact of damaging cuts.” And at least some rehiring will be necessary to maintain the current staffing levels at the federal level: based on previous budgetary allocations, Statistics Canada predicted a loss of 406 jobs at the Department of Environment and Climate Change, but those numbers are based on budgets from the Harper Administration. It remains to be seen how those predictions will play out after the multimillion dollar budget boost the department received earlier this year.

Learning Curves

With the lack of government-funded research of the last decade, many Canadian researchers are concerned about the ability of the Canadian government to effectively assess grants and award research dollars, which was expressed this past summer when more than 1,300 researchers signed an open letter to the CIHR in protest over recent changes to the evaluation phases of the federal government grant cycles. The CIHR had made changes intended to streamline the review process, but instead resulted in reviewer-subject area mismatches and the disfavoring of women scientists, young researchers, and basic science researchers. While the government attempted to react to problems and concerns, the new process resulted in the cancellation of two grant cycles and a grant rejection rate of 87%.

With the lack of government-funded research of the last decade, many Canadian researchers are concerned about the ability of the Canadian government to effectively assess grants and award research dollars, which was expressed this past summer when more than 1,300 researchers signed an open letter to the CIHR in protest over recent changes to the evaluation phases of the federal government grant cycles. The CIHR had made changes intended to streamline the review process, but instead resulted in reviewer-subject area mismatches and the disfavoring of women scientists, young researchers, and basic science researchers. While the government attempted to react to problems and concerns, the new process resulted in the cancellation of two grant cycles and a grant rejection rate of 87%.

In spite of these issues, Dr. Robaire remains optimistic: “What’s impressive is that the government did respond to the scientists’ concerns about what the CIHR was doing,” he says. “[Canadian Health Minister Jane Philpott] realized that the governing council of that agency clearly made mistakes, and they had to listen to the community and respond to it.”

Dr. Duncan’s response has been to commission what is being referred to as the Naylor Report, “an independent review of federal funding for fundamental science. The review will assess the program machinery that is currently in place to support science and scientists in Canada.” This review, led by former University of Toronto President David Naylor, MD, DPhil, FRCPC, will examine the three major federal granting agencies (CIHR, NSERC, and the SSHRC) and other select federally funded organizations, in an effort to “optimize support for fundamental science in Canada.”

From the funding injections to the restoration of the minister of science post to the Naylor Report, the overall emphasis on basic science and restoration of appropriate funding levels has encouraged many Canadian researchers, “The real test will be the government’s response to the Naylor Report,” says Robaire. “That will tell us how serious the government is about funding research. My guess is that we’ll see a significant response, but that’s only a guess.”